People are familiar with the prisoner’s dilemma in game theory. This is a setup where two accomplices are caught at the same time. Police separate them and give each an offer: to defect on their accomplice - meaning blame them, or to stay quiet.

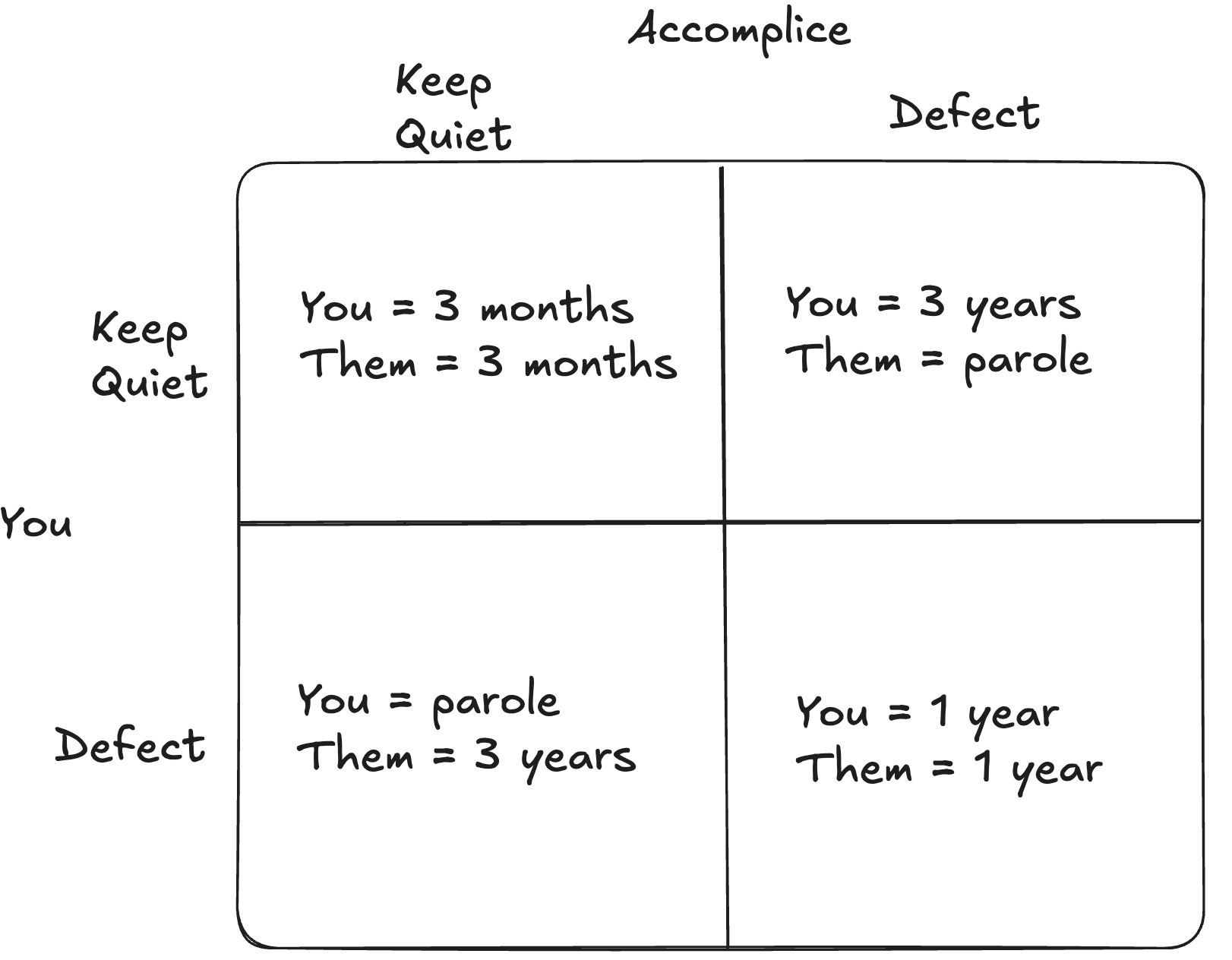

If you both stay quiet, the police have nothing on you except petty crime, and you’ll go to jail for 3 months. If you both defect, they’ll have proof on both of you, and you’ll both go to jail for 1 years. But if one defects and the other stays quiet, the one who defected will walk away with no jail time, while the one who stayed quiet will get 3 years. See game theory ‘payout’ matrix below.

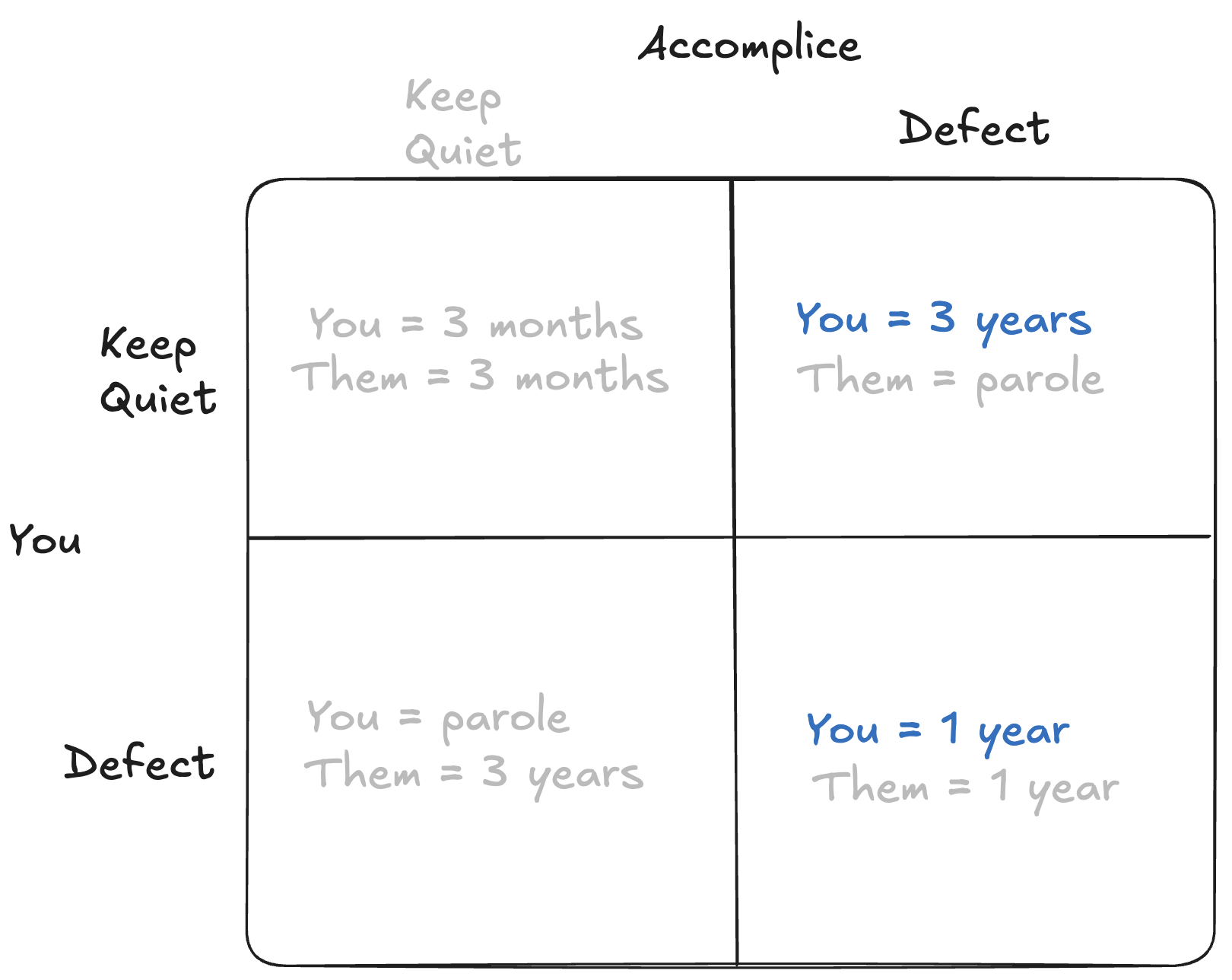

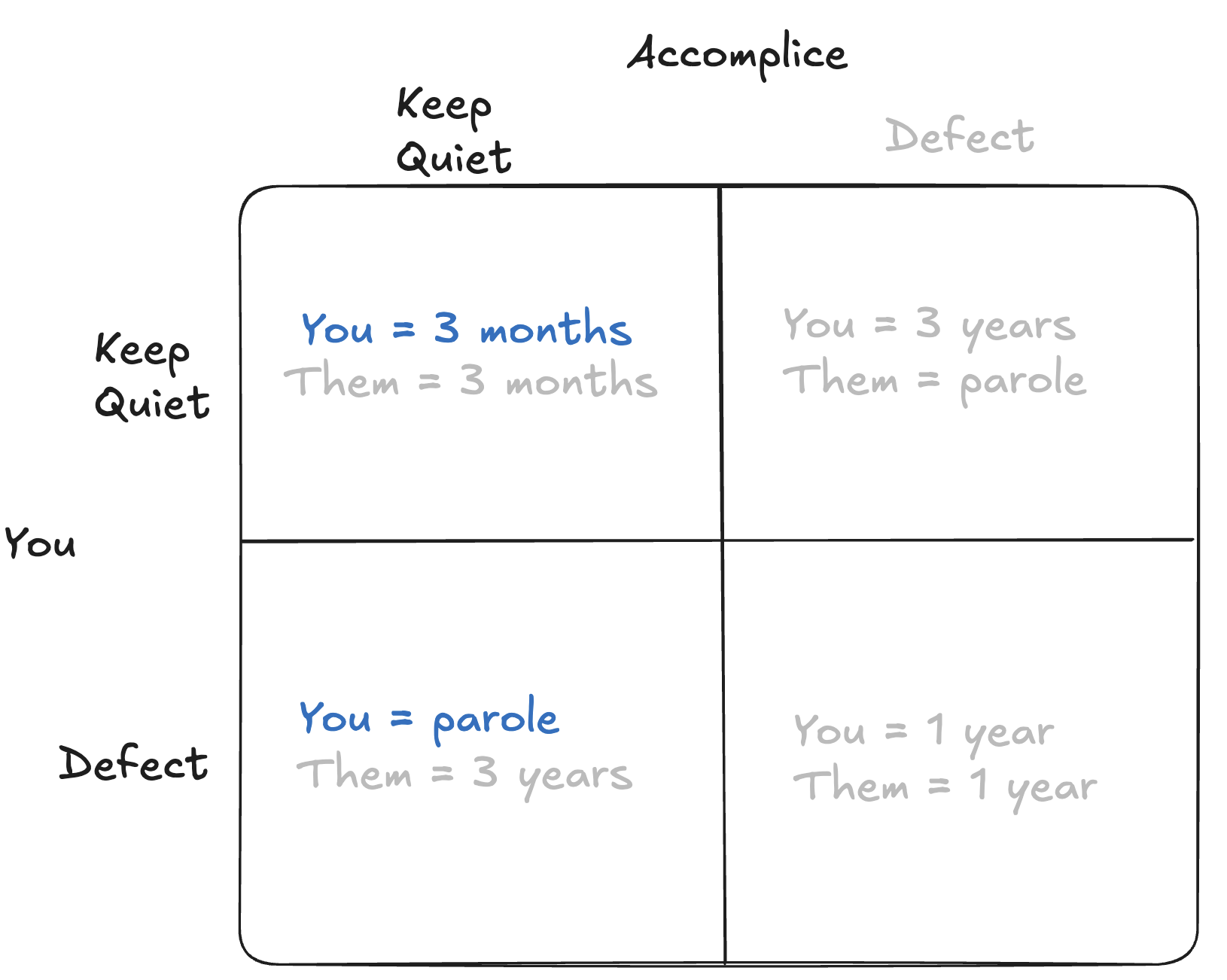

The game theoretically ‘correct’ position in a single round of this situation is to defect and blame your accomplice. You don’t know what they will do. First, assume he defects. In that case your options are to defect as well (which will get you 1 year in jail) or to keep quiet (which will get you 3 years in jail). It’s clear 1 year is less than 3, so you should defect.

And now, let’s say your accomplice keeps quiet. Then your options are to also keep quiet (just 3 months!) or to defect (no jail time). No jail time is better than 3 months, so you should defect.

So the core gotcha of the prisoner’s dilemma is that the equilibrium appears to be for you both to defect and you end up in jail for 3 years each, instead of what would seemingly be a better situation of just 3 months of jail.

Iterative games are different

Some people read this and immmediately react that this is not how criminal enterprises actually work (or at least the successful TV ones). Certainly Tony Soprano would not keep folks who defected around for long.

And economists have long studied this situation. In fact, the dilemna was formalized as part of research by RAND Corporate into conditions that would lead to cooperation instead of nuclear war. The history is fascinating and worth a read!

The core insight is that defection makes sense when there is a single round, e.g ‘one shot’ to keep quiet or to defect. If, instead, you have infinite rounds it favors cooperation, because you will be playing similar games with either the same person (trust) or people who know you (reputation) and you will end up with better results with cooperation.

Whenever you can, play iterative games

Okay, so, why am I writing about this in a mostly tech career blog? Fundamentally, as you navigate your career, you need to think about every interaction as a repeat game. If you accidentally fall into one-shot prisoners dilemna behavior you will harm your reputation and damage future long-term opportunities. I use this framework for actions big and small, including:

- Spend political capital time, and energy to give full credit and support to others vs taking credit for yourself

- Default to being helpful, trusting, and honest when people seek your guidance

- Say when you don’t know something

- Don’t sandbag estimates for project completion or sales. Similarly, don’t overpromise

- Be transparent and clear about a roles positives and negatives hiring and selling candidates on a job

- Focus on optimal outcomes for your customer and business, don’t work backwards from your personal career goals

- When leaving a company give reasonable notice and manage a professional transition

Reading this you may feel that these behaviors are correct in theory, but many of us have experienced folks getting ahead unethically in ways big and small, taking vs giving credit, backstabbing peers to leaders, or even just overpromising then blaming others. Simply, you should make sure to only work in organizations that are not like this. And, as a leader, the most important thing you can do to lead an effective organization is to properly setup incentives towards cooperations vs defection.

How to make your organization’s games iterative?

Economists define conditions that support cooperations as:

- Unknown or infinite round games: this is the core insight. Single round games have no incentive to build a cooperative reputation. Similarly, no clear ‘final’ round.

- Ability to remember past actions: combined with (1) this ensures that players will cooperate better with folks that cooperate well with them.

- Sufficient value of future payoffs: players must care about future rewards. The opposite is if the current situation is so valuable relative to the future that they are willing to damage future games.

- Possibility of punishment: negative version of (3) - if there are serious future adverse results in downstream rounds players will cooperate better now.

Which does neatly represent how the best tech investors behave most of the time. Their reputations are critical to the next startup’s decision of who to take funding from (YC specifically and transparency generally has only increased this). Thank you to IA Ventures, Background Ventures, and Addition Ventures for their support as I wound down Proximo Data!

Outside tech investing, as an organization leaders we must encourage cooperation instead of defection by:

- Unknown or infinite round –> high retention rates ensures that more people involved are considering their future reputation. Positively helping people find their next job, giving referrals, and being open to boomerangs.

- Ability to remember past actions –> most simplify, cooperation vs defection behavior must be shared via public feedback or open discussion. A useful mechanism for this is in project retros or hotly debated topics. Overpromising and then making excuses can be dealt with a calm public nudge ‘seems like we underestimated the complexity here, how can we do better going forward?’

- Sufficient value of future payoffs –> in selecting project leads for exciting and risky projects, leaders should consider not just short-term results, but the mechanisms folks in the org used to acheive them.

- Possibility of punishment –> when evaluating performance and giving constructive feedback, leaders must include specific repurcussions for non-cooperative behavior.

Assuming you have acheived an iterative game, leaders need to make sure they are creating the long-term incentives they intend. Too much rewards for short-term results will reward incrementalism and punish risk-taking. Constantly doubling down on funding for projects behind schedule with excuses rewards overpromising. Offering significant compensation bumps only if staff get external offers encourages folks to be constantly interviewing. Remember that each decision is an iterative game, avoid optimizing for putting out the current fire and think about the long-term incentive your decision is creating.

Note - all of the above talks about cooperation not ‘collaboration’. I am skeptical that teams need to always actively collaborate. A strength of Amazon was simplifying coordination from meetings into APIs so each stream-aligned team can determine independently the best way to serve customers, reducing a lot of collaboration cost.